“Surrey has big aspirations,” according to Scott Groves, who oversees the design, construction, and operation of all civic facilities in Surrey. The burgeoning metropolis, located between the Fraser River and the Canada – United States border, is now the province’s fastest-growing city.

Once considered a suburb, Surrey is now arguably the region’s emerging second downtown: its population of over half a million is growing at twice the rate of Vancouver’s, and is set to eclipse it by 2030 to make Surrey the largest city in the province.

“Surrey is a diverse city that speaks over a hundred different languages. We want to connect our citizens, share our cultures, and break down barriers,” Groves says.

Within the last decade, the City of Surrey has made significant investments in civic and community buildings, many of which not only incorporate wood and mass timber, but represent boundary-pushing, world-class architecture. This is thanks in part to a Wood First Policy that the City adopted in 2010, which recognizes wood’s social, environmental, and economic benefits, and makes it the material of choice for public buildings.

It seems fitting and fortuitous that Groves grew up in B.C.’s South Cariboo region in the town of 100 Mile House, the self-proclaimed “handcrafted log home capital of North America.” His family’s first business was building heavy-timber log houses. “My very first real job was making the pieces of wood that would serve as the balcony rails for log cabin homes. At the age of thirteen, I’d go out and cut down small trees, strip the bark off, and sell the poles to my uncle,” Groves recalls.

Between semesters at the University of British Columbia, where he completed a civil engineering degree, Groves worked as a tree planter, another experience that he believes reinforced his affinity for nature and wood. “My upbringing, and where I grew up, I think it definitely gives me a different perspective and an appreciation for nature and wildlife—a connection that is, perhaps, a little deeper for me. I don’t know how many tens of thousands of trees I planted in this province but I’m proud to have been part of that,” says Groves.

Before joining the City of Surrey, Groves worked as a civil engineer on the Richmond Olympic Oval and for the Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Since then, he’s played an important role in Surrey’s “If we build it, they will come” strategy, which appears to be working: the city is gradually transforming from a mostly automobile-centric suburb to a metropolitan city with walkable, transit-friendly town centres.

For Groves, it’s about connecting the increasingly dense and diverse communities of Surrey, in a day and age when people can feel isolated. “Today, more and more people live in homes or condos where they don’t have enough room for a garage, workshop, or studio anymore and, at the same time, we often don’t tend to meet or rely on our neighbours as much either. Civic and recreational facilities are becoming an extension of our living space, a kind of community living room in some ways,” he says.

And Groves believes making those spaces warm, welcoming, even awe-inspiring, is crucial to their success — and wood, he explains, has a distinct role to play, adding intangible value that goes beyond mere construction costs.

“We need to make these facilities places people want to be in, and using wood is a part of that. Pre-engineered manufactured open-web steel-joist construction might be cheaper, in some cases, but on its own it would fail to meet the objectives of most projects. You wouldn’t achieve civic pride and it wouldn’t create a place where people want to hang out and connect with their community. To be successful, we want it to feel like an extension of your living room.” He adds, with a chuckle, “and people don’t make their living rooms out of metal.”

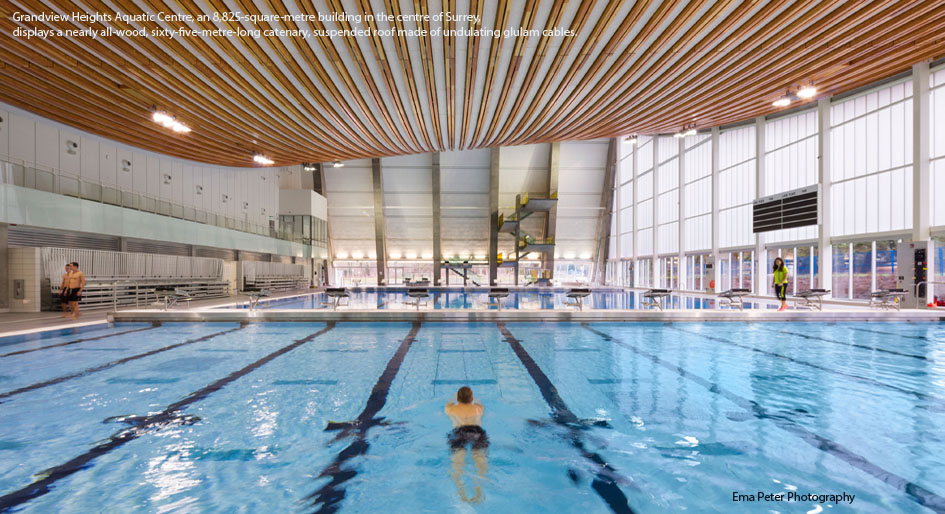

One particularly successful example is the Grandview Heights Aquatic Centre. Designed by HCMA Architecture + Design, the 8,825-square-metre building boasts a nearly all-wood, sixty-five-metre-long free-hanging curved roof, the longest clear span of its kind to date.

“We’re very proud of Grandview Aquatic Centre. Visitors almost feel like they’re swimming outside and that’s an experience that people don’t get so much anymore. It’s because of a number of factors—it has a spacious, open feel, the ceiling is so high and it has this great wood structure,” he explains. “Because it has so many glue-laminated timber (glulam) and because they use them as cords, you stand at one end of the lap pool and it creates this interesting optical illusion, making it look even larger, more expansive. It turns out wood works really well in tension. It’s a brilliant design.”

Equally successful, but distinct in its design, is the Guildford Aquatic Centre by the late architect Bing Thom. The all-white, prefabricated, twenty-nine-metre-long wood trusses (made from laminated strand lumber) show how wood can be unmistakably modern in its aesthetic, while solving a common operational problem. By neatly tucking away pre-installed mechanical ducts, sprinklers, uplighting, and acoustic ceiling insulation into the trusses, maintenance staff can access mechanical services or change a light bulb without having to shut down the pool, a simple cost savings that Groves appreciates.

But the project he seems most excited about is just breaking ground. Designed to be a seven-thousand-square-metre hub for its fast-growing, demographically diverse neighbourhood, Clayton Community Centre challenges conventional civic design principles by combining recreation, library, arts, and parks spaces into a single facility centred on an atrium that could be likened to a modern-day piazza.

Wood will be a primary component of the design, and in fact offers cost savings for the futuristic community centre. When there was pressure to reconsider steel as a structural solution to save money, Groves pushed back. After some number crunching, it turned out the steel option posed more risk, with the potential for significant cost overruns. “Using wood wasn’t more, and in fact could save us money in the long run,” he remarks.

Beyond cost, Groves explains that retaining the park-like feel of the site and incorporating wood into the structure was important to the community. “They told us they didn’t want to lose the park and the trees, so part of the goal of the design is to bring the forest into the building. The atrium will serve as a kind of extension of the canopy of the forest nearby and the glulam and pinwheel design creates a leaf- and branch-like structure. We want to connect the community and connect that community to nature. Using wood in this project was a big piece of that.”

And, perhaps more than anything, Clayton Community Centre reflects the civic aspirations and ideals of a richly diverse, spirited, and progressive metropolis—one that is investing in its long-term future and, most importantly, in its citizens.

Download your Naturally Wood digital copy here.