Newly released updates to the ASHRAE standards for ventilation and indoor air quality (IAQ) in commercial and residential buildings underscore that outdoor air is not necessarily synonymous with freshness. Guidance related to natural ventilation, particulate filtration and compartmentalization of multi-residential HVAC systems to support more direct and efficient air exchange are prominent in the list of identified “significant changes” compared to the incumbent 2016 version of the standards that are widely referenced in building codes around the world.

“These standards have undergone key changes over the years, reflecting the ever-expanding body of knowledge, experience and research related to ventilation and air quality,” says Jennifer Isenbeck, chair of the ASHRAE committee overseeing the development of standard 62.1-2019, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality for non-residential buildings. “The purpose of both standards remains unchanged, yet the means of achieving this goal have evolved.”

For commercial buildings, that includes: new procedures and assumptions for calculating system requirements; criteria specific to certain types of occupancies, such as outpatient health care facilities, which weren’t singled out previously; new requirements for intake and integration of outdoor air; and a prohibition on air-cleaning devices that generate ozone. Dew point temperature will replace relative humidity for expressing humidity levels, which is considered a more precise and appropriate metric.

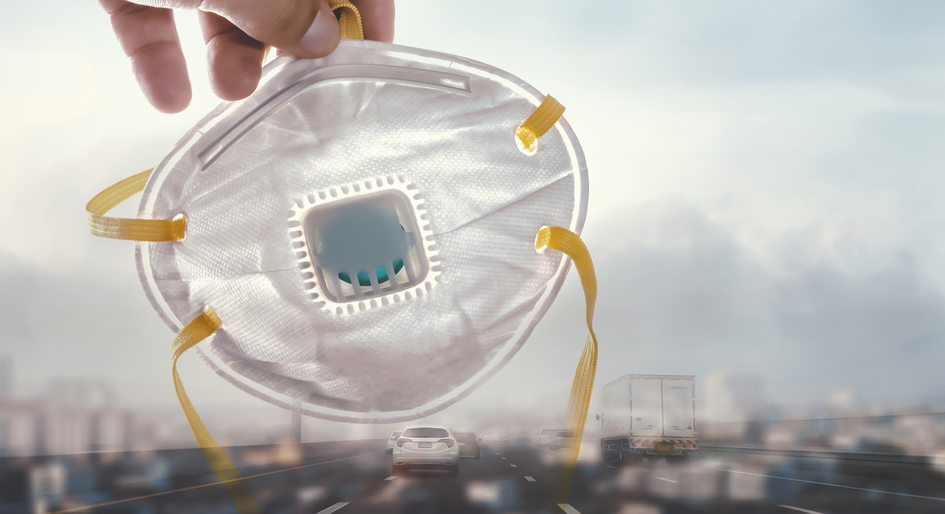

The new regimen for natural ventilation is in sync with green and resilient building pressures to curb reliance on mechanical ventilation systems, while accounting for contaminants and other destabilizing factors outside buildings.

“Requirements for natural ventilation design instruct designers to consider outdoor air quality — whether smoke from wildfires or particulates, as is common in Beijing, London and other major cities — and to consider the interaction of outdoor air with mechanically cooled spaces. Bringing in outdoor air in hot humid locations, like Dubai, for example, can create significant condensation problems in mechanically cooled interiors,” explains Alex McGowan, an engineer and senior manager with WSP’s building sciences group.

“The green building movement brought natural ventilation back to designs, perhaps with some disregard to outdoor air not being so fresh. We need to consider that windows will be closed and how to keep IAQ at a reasonable level for occupants,” says Andrew Pride, an engineer and specialist in energy efficiency, sustainability and green project facilitation. “These ASHRAE changes are a breath of fresh air, and I think they will complement smarter controls that understand when a space is occupied in order to trigger outdoor air ventilation.”

Likewise, standard 62.2-2019, Ventilation and Acceptable Indoor Air Quality in Residential Buildings, reflects that progressive, energy-efficient multi-residential building design has evolved away from ventilation via corridor pressurization systems, allegedly delivering air through facing doorways, in favour of heat recovery ventilators (HRVs) or energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) in each suite.

“Cool innovations like HRV-fan coils started a new movement in Toronto condos, offering better IAQ and energy savings in one space-saving device,” Pride notes.

The updated standard stipulates compartmentalized, in-suite ventilation in newly constructed multi-residential buildings and requires designers to consider outdoor air in the context of balanced — i.e. intake equals exhaust — and unbalanced ventilation. It also allows for an alternative compliance path with extra controls for particulate filtration.

“It will be important for property managers to service and clean the filters on a regular basis,” Pride advises. “Positive intentions, such as good air quality from HRVs or ERVs, can be undone by poor service.”

As with other types of sustainable and energy-efficient features, McGowan projects that resulting operating cost savings should compensate for the likely higher capital costs to comply with the standards.

“Some items will be more challenging due to the additional design considerations, but, arguably, these things should always have been considered, if we have the right information,” he maintains. “At the same time, some design procedures have been simplified, which is good.”

Although ASHRAE’s pace in producing updated versions of its standards is famously faster than most building code cycles, McGowan suggests the 2019 iteration of the 62.1 and 62.2 standards could soon be referenced and show up in various building certification prerequisites or credits. “Some codes refer to the latest version of the pertinent standard, which keeps designers on their toes,” he affirms.

Barbara Carss is editor-in-chief of Canadian Property Management.